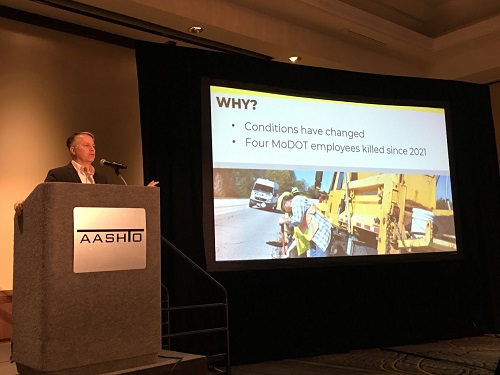

At the 2023 Safety Summit hosted by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials in Kansas City, MO, state department of transportation executives outlined the steps required to make positive changes to the roadway safety culture of the United States.

[Above photo by AASHTO]

“The reality is our highways are not what they used to be. For this [the smartphone] has changed the roadway culture,” explained Patrick McKenna, director of the Missouri Department of Transportation, chair of the AASHTO Committee on Safety, and a former AASHTO president.

“We know that if [motorists] put their phones down and buckled up, we’d cut roadway fatalities in half,” he said. “But as much as we try, we are not necessarily seeing changes in public behavior. So what do we do in response to this safety crisis?”

McKenna said the first step for Missouri DOT was to mirror internally the safety culture it espoused in public.

“We must have an employee base that walks the talk,” McKenna noted – meaning that while at work, they must buckle their seat belts and follow the speed limit, or risk termination.

“Because we said what we meant and meant what we said, we had improvement,” he pointed out. “You will get feedback; you will have resistance; but you have to push through it. This requires a sustained effort. Because you can’t compromise on safety. Instead of a bitter lesson, you could be facing a tragedy and a funeral. That’s why changing the safety culture takes everyone – you can’t have pockets of resistance – and your employees are watching. As soon as you look the other way for someone, you set your entire safety culture back.”

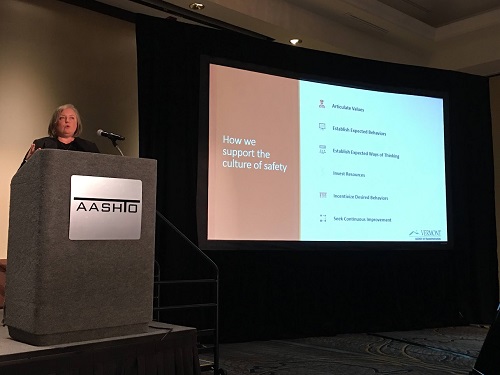

Jayna Morse, director of finance and administration for the Vermont Agency of Transportation (known as VTrans), said that means safety must be woven into values of state DOTs yet not be seen as a burden.

“What creates strong safety culture? Strong leadership. We have to set the standard and emulate how we want culture to be – we have to demonstrate it and buy-in from leadership sets the tone,” she explained. “People are our most important asset and we need to make sure they all go home safe at the end of the day.”

To do that, Morse said VTrans piloted a shift from being “compliance officers” to “advisors” where safety is concerned. “We look to give advice on how to be safer and look at things with an eye to how to teach safety and build ‘whole-health’ picture for employees.”

She said that perspective helped cut VTrans workplace injuries by half since 2017. Yet building an all-encompassing safety culture takes time to implement, she stressed.

“Building trust takes time,” Morse said. “It means articulating our safety values clearly and constantly supporting them, from leadership on down.”

Jason Siwula, deputy state highway engineer at the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, pointed out that there can be “no daylight” between safety and every other aspect of state DOT operations.

“Every single action you take every day sets an example – so what example are you setting?” he asked. Siwula noted that Jim Gray, KYTC’s secretary, emphasized that clearly articulating the importance of safety first is critical to achieving long-term safety culture changes.

“’A good plan is like a road map – and the journey is the safest when the road map is clear,’ is what our secretary says,” Siwula pointed out. “Is safety part of your conversation when you talk about work? Because the things we talk about at safety meetings are typically not what gets discussed at other meetings – and that should not be. Another thing: Will these safety policies survive past leadership tenure if they are just mandated from the top down? That’s what creating a lasting safety culture is all about.”

Top Stories

Top Stories

EPA Withdraws 2009-Era GHG ‘Endangerment Finding’

February 13, 2026 Top Stories

Top Stories