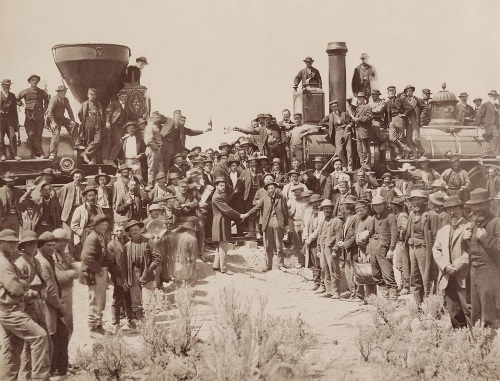

The competition of the First Transcontinental Railroad across the United States – originally called the Pacific Railroad – officially occurred on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit in what was then the Territory of Utah when the tracks of the eastbound Central Pacific Railroad joined those of the westward Union Pacific Railroad. It took 16 long years to build what eventually became a 1,912-mile-long coast-to-coast railroad line.

[Above photo via the Yale University Libraries.]

“The long-looked-for moment has arrived,” reported the New York Times on May 11, 1869. “The inhabitants of the Atlantic seaboard and the dwellers on the Pacific slopes are henceforth emphatically one people.”

As part of the festivities at Promontory Summit, the Union Pacific No. 119 steam locomotive from the east and the Central Pacific No. 60 steam locomotive from the west – better known as the Jupiter – were drawn up face-to-face with each other on tracks that would soon be fully connected.

Those speaking at that day’s ceremony included Leland Stanford, CPRR’s president and former California governor, who extolled both the historical significance and economic benefits of the new coast-to-coast railway network.

“This line of rails connecting the Atlantic and Pacific, and affording to commerce a new transit, will prove, we trust the speedy forerunner of increased facilities,” he said. “The Pacific Railroad will, as soon as commerce shall begin fully to realize its advantages, demonstrate the necessity of such improvements in railroading as to render practicable the transportation of freights at much less rates than are possible under any system which has been thus far anywhere adopted.”

Indeed, the new cross-country railroad proved to be pivotal development in American history – reducing a six-month trip to California from the east to no more than two weeks and in the process significantly shrinking distances between various sections of an ever-growing nation.

Not long after Stanford’s remarks on that dusty Monday afternoon 150 years ago, one set of laborers laid down and linked the last two rails for the UPRR, with the last two rails on the CPRR side finished off by another set of workers. At around one o’clock, a total of four ceremonial spikes – two of them gold, one of them silver, and another a blend of gold, silver, and iron – were tapped by dignitaries into a railroad tie made of laurelwood.

It was Stanford who tapped in the final of those spikes – a gold one that is now famous as the “Golden Spike” or “Last Spike” that represented the final link in the transcontinental rail line. Yet the laurelwood tie and its precious-metal spikes were quickly replaced by four iron spikes and a tie made from pine prior to full-fledged operation of the line.

News of this transportation milestone was quickly circulated via telegraph across the United States, and the overall response was one of sheer exuberance.

Celebratory cannons boomed in San Francisco and Washington, D.C., for example, and bells rang throughout Philadelphia. Stanford and UPRR Vice President Thomas Clark “Doc” Durant jointly sent a telegram to President Ulysses Grant to update him on events at Promontory Summit, stating simply: “We have the honor to report that the last rail is laid, the last spike is driven, the Pacific Railroad is finished.”

For more information on the First Transcontinental Railroad, please check out https://www.up.com/goldenspike/index.html and http://www.tcrr.com/

Nation

Nation

Registration Open for AASHTO 2026 Spring Meeting

March 13, 2026 Nation

Nation