Raising fuel taxes is currently the most direct and efficient way to generate the money to funded overdue investments in Ohio’s transportation system, though a decade down the road, a vehicle miles traveled or VMT fee might prove to be a more viable option.

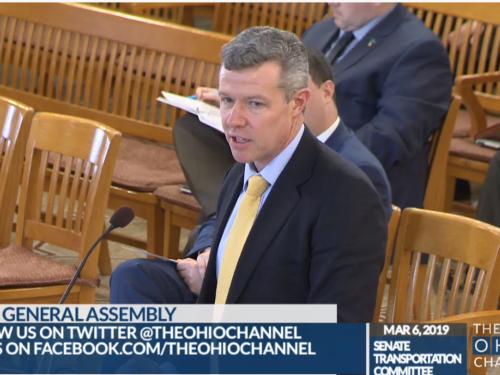

Those were just two of several points Jim Tymon (seen above), executive director of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, stressed in hearings before the Ohio House of Representatives Finance Committee on March 5 and the Ohio Senate Transportation, Commerce, and Workforce Committee on March 6 as legislators contemplate the proposal by Gov. Mike DeWine (R) to boost the state’s fuel tax by 18 cents per gallon.

[Above photo via screen capture from Ohio Channel Live broadcast.]

“Nationwide, we see ample evidence for ever-growing transportation investment needs from growing population, aging infrastructure stock, and rapid deployment of new technology,” Tymon said in his remarks. “In 1970, Americans logged just over 1 trillion VMT; yet by last year we traveled over 3 trillion miles. By 2030 we are expected to see a 25 percent increase in VMT and a 64 percent increase in travel by large commercial trucks.

But he told Ohio lawmakers that even as the demands on the nation’s transportation network increase every year, not enough is invested to offset them. For example, Tymon said 33 percent of major urban roads in the United States are now in “poor condition” and more than half of all bridges in the U.S. are rated either “fair” or “poor.” On top of that, the average American spent 97 hours sitting in traffic in 2018, costing the economy $87 billion in lost productivity.

“Drivers right here in Columbus wasted 71 hours sitting in traffic last year, costing them nearly $1,000,” he added.

At the same time, the price tag to bring the surface transportation system up to a good state of repair is rising. According to the US Department of Transportation’s 2015 Conditions and Performance Report to Congress, the highway and bridge “investment backlog” has reached $836 billion, breaking down into $420 billion for highways, $123 billion for bridges, $167 billion for system expansion, and $126 billion for system enhancement.

Meanwhile, the federal fuel tax on both gasoline and diesel hasn’t been increased since 1993, while at the state level, Ohio has not raised its fuel tax since 2005. In that 14-year span, Tymon pointed out, some 35 states and the District of Columbia increased their fuel tax.

“I will say raising taxes is tough – Congress had the opportunity to do so five years ago [when it passed the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation or FAST Act] but it chose not to, dipping instead back into the general fund,” he explained to the Ohio Senate Transportation Committee.

“Congress is really struggling with this because the federal transportation program is funded through the Highway Trust Fund, which is spending $15 billion more than it is bringing in in revenue,” Tymon noted. “That is forcing Congress to sit back and figure out future funding, because just to maintain the current level of spending, it will need to raise the [federal] gas tax by 12 to 15 cents [per gallon]. That will make it harder to get [FAST Act reauthorization] done on time.”

Yet he stressed that, as of now, the “most efficient way” to raise revenue for highway investment is to increase the fuel tax at both federal and state level. “It is the best proxy for vehicle use we have right now, because the more you drive, the more fuel you need to buy,” he noted. “It is the best option right now.”

Down the road, though, switching to a VMT fee may prove to be the more practical option in terms of charging a “user fee” for using the surface transportation system – especially for vehicles that are not powered by gasoline or diesel.

“Many states in the Northwest in particular are piloting testing VMT fees,” Tymon said. “The technology isn’t the barrier – the problem we’re finding is the public’s privacy concern associated with the government knowing all of the miles you are traveling. That’s one reason many states are participating in VMT pilot programs right now; not only to prove the technology exists and works but to get their residents comfortable with technology.”

Yet while VMT fees may prove a “viable option” for surface transportation funding in the future, he emphasized that “it is not ready for prime time” quite yet.

“The technology is there to plug into vehicles and track miles, but for it to actually be incorporated into the majority of vehicles will take time,” Tymon noted. “It takes the entire vehicle fleet 10 to 15 years to turn over – so we’re not ready to move exclusively in that [VMT] direction for another 10 years.”